1.6. Relational graphs: scatter plots¶

This is a plot many people are comfortable using. It helps you understand the relationship between two variables - a bivariate plot - as opposed to the previous charts that are univariate. A scatter plot is a collection of points shown inside a box formed by two axes at 90 degrees to each other. The marker’s position is located at the intersection of the values shown on the horizontal (x) axis and vertical (y) axis.

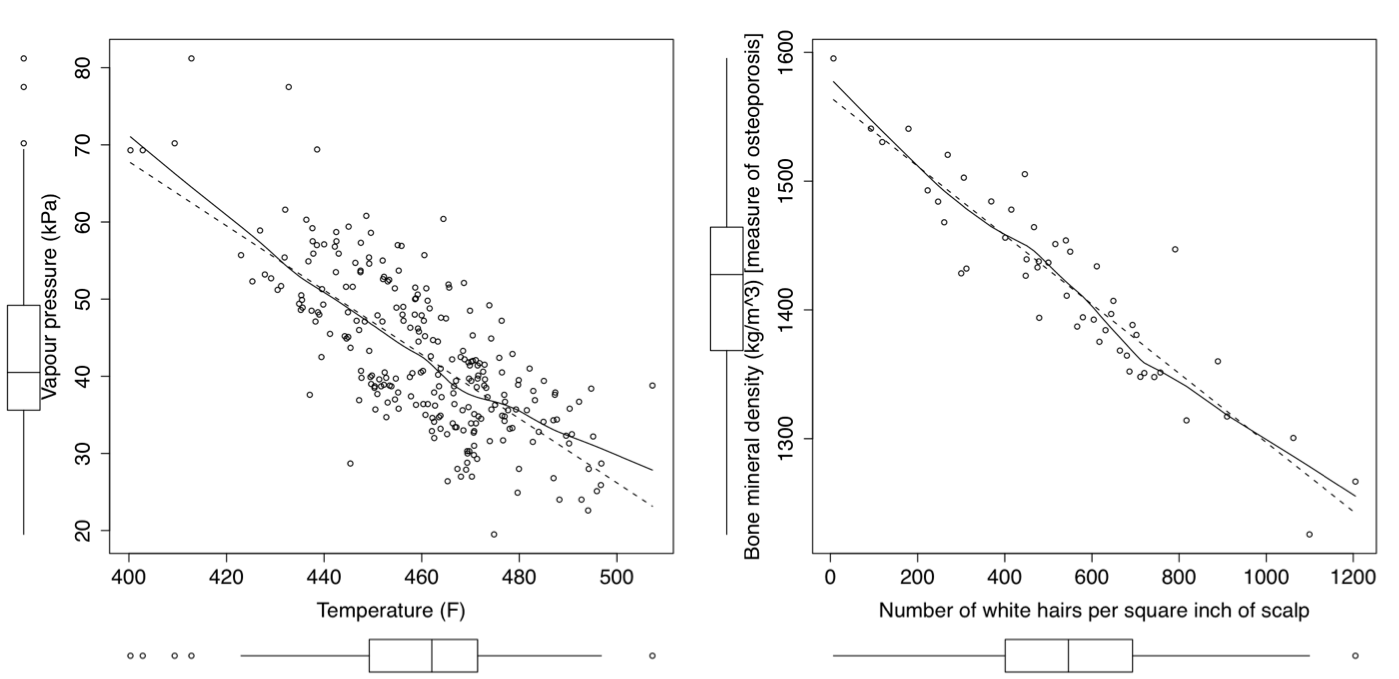

The unspoken intention of a scatter plot is usually to ask the reader to draw a causal relationship between the two variables. However, not all scatter plots actually show causal phenomena, as the figure below tries to convince you:

This source code generates similar, but not identical, figures to those shows here in the text.

The equivalent code in Python:

Strive for graphical excellence by doing the following:

Make each axis as tight as possible.

Avoid heavy grid lines.

Use the least amount of ink.

Do not distort the axes.

There is an unfounded fear that others won’t understand your 2D scatter plot. Tufte (Visual Display of Quantitative Information, p 83) shows that there are no scatter plots in a sample (1974 to 1980) of U.S., German and British dailies, despite studies showing that 12-year-olds can interpret such plots: Japanese newspapers frequently use them.

You will see this in industrial settings as well. The next time you go into an industrial control room (or look carefull at some screens in online videos), try finding any scatter plots. The audience is not to blame: it is the producers of these charts who assume the audience is incapable of interpreting them.

Note

Assume that if you can understand the plot, so will your audience.

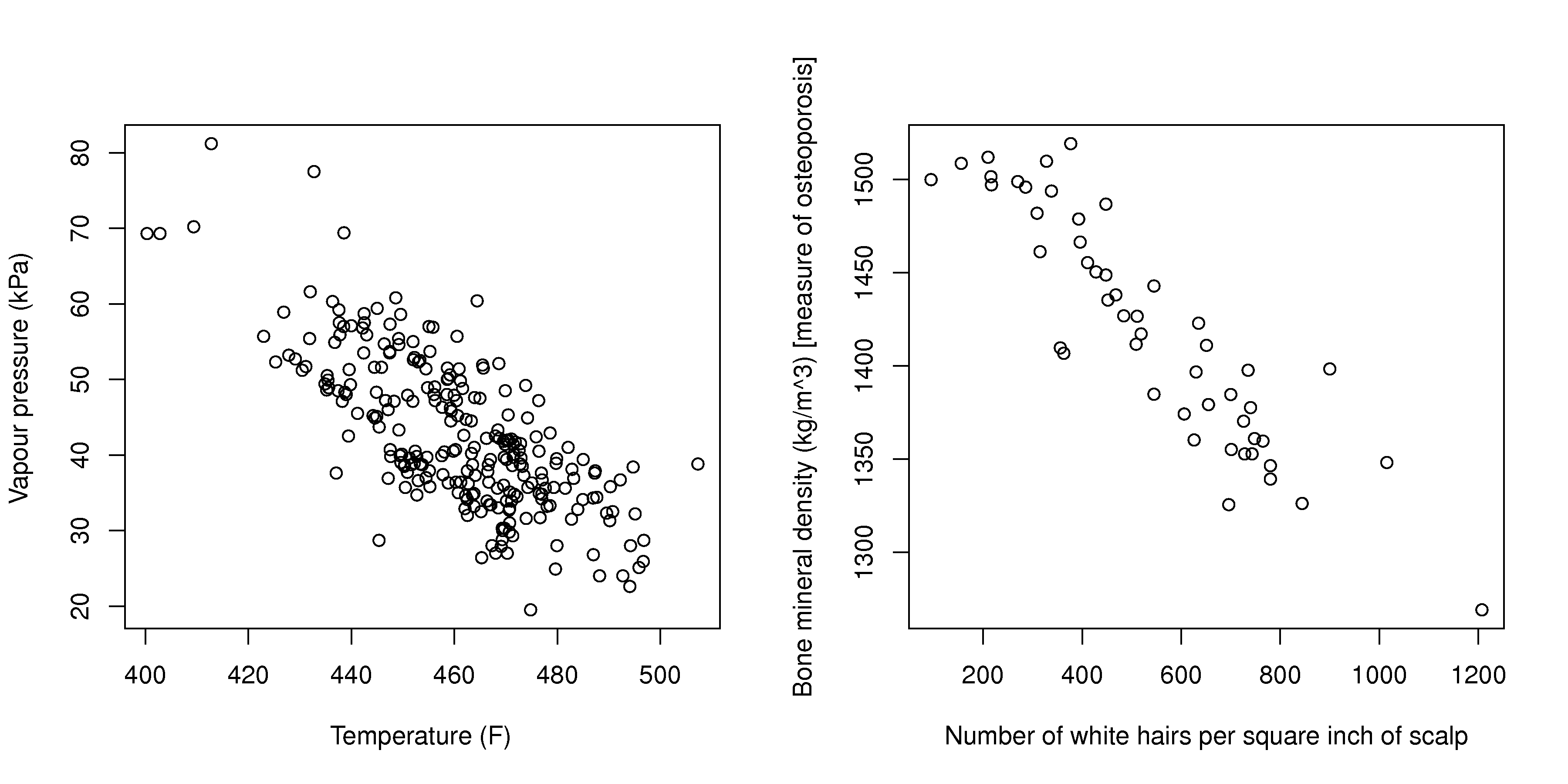

Further improvements can be made to your scatter plots. For example, extend the frames only as far as your data:

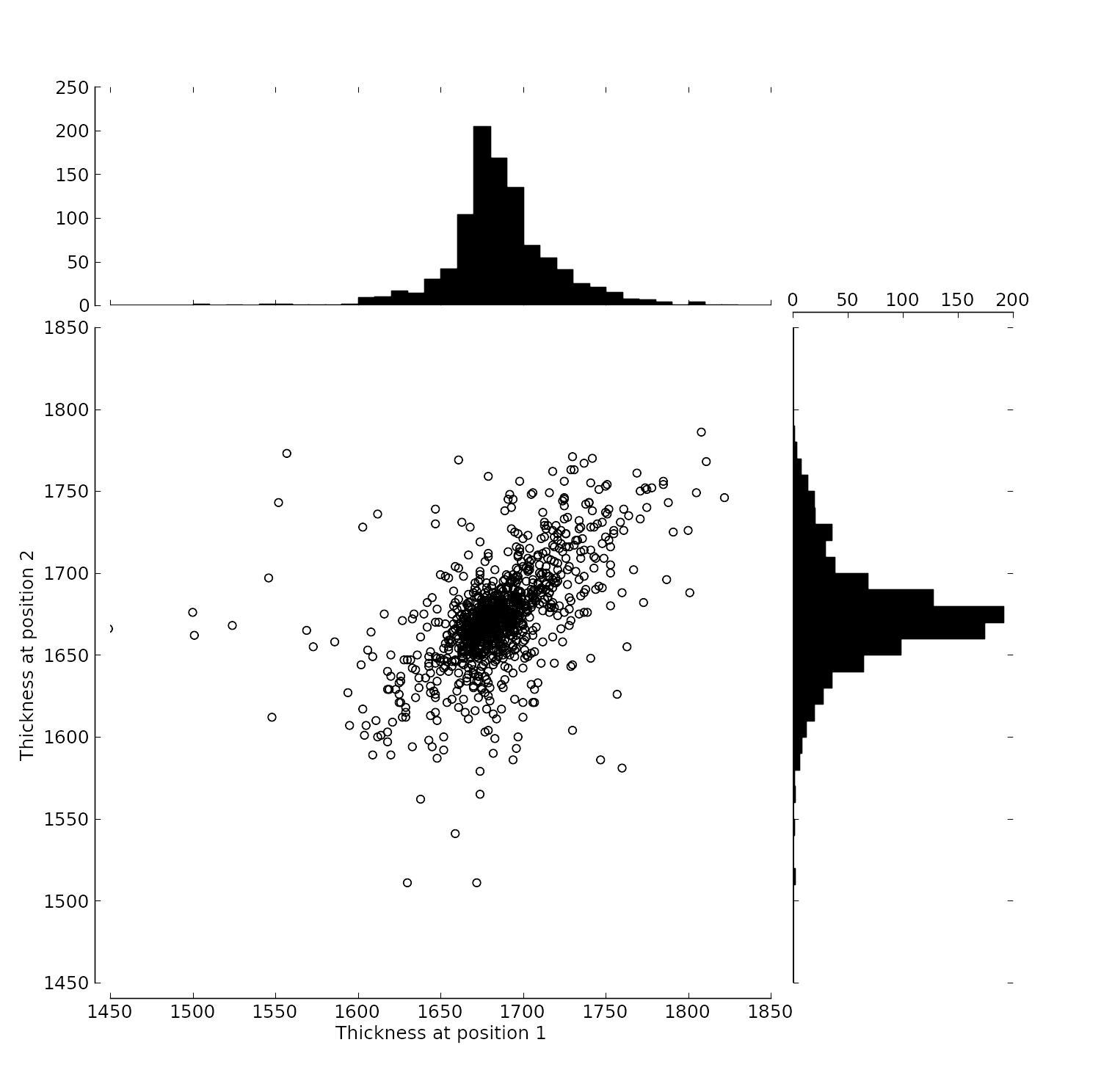

You can add box plots and histograms to the side of the axes to aide interpretation:

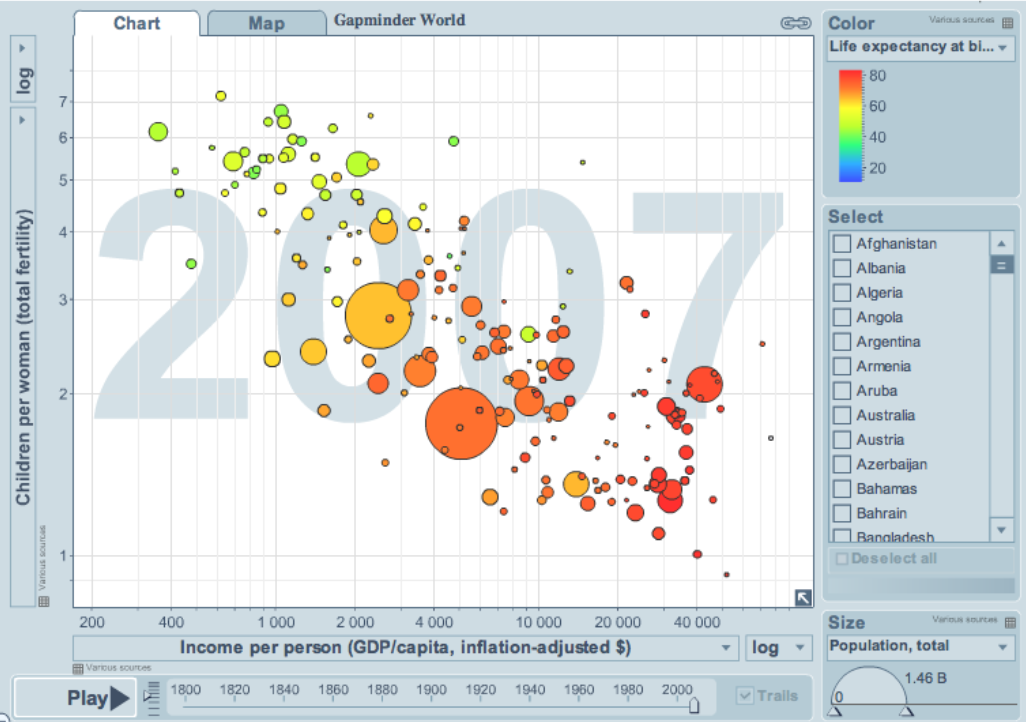

Add a third variable to the plot by adjusting the marker size, and add a fourth variable with the use of colour:

This example, from https://gapminder.org , shows data until 2007 for:

income per person (x-axis);

against fertility (y-axis);

the size of each data point is proportional to the country’s population;

the marker colour shows life expectancy at birth (years).

The GapMinder website allows you to “play” the graph over time, effectively adding a fifth dimension to the 2D plot.

So 5 dimensions in a 2D surface. A 6th dimension cab be added if using technology such as VR glasses, to create a 3rd dimension, to display another variable from the data set.

Use the hyperlink above to see how richer countries move towards lower fertility and higher income over time.