5.6. Experiments with a single variable at two levels¶

This is the simplest type of experiment. It involves an outcome variable, \(y\), and one input variable, \(x\). The \(x\)-variable could be a continuous numeric one, such as temperature, or discrete on, such as yes/no, on/off, A/B. This type of experiment could be used to answer questions such as the following:

Has the reaction yield increased when using catalyst A or B?

Does the concrete’s strength improve when adding a particular binder or not?

Does the plastic’s stretchability improve when extruded at various temperatures (a low or high temperature)?

We can perform several runs (experiments) at level A, and some runs at level B. These runs are randomized (i.e. do not perform all the A runs, and then the B runs). We strive to hold all other disturbance variables constant so we pick up only the A-to-B effect. Disturbances are any variables that might affect \(y\) but, for whatever reason, we don’t wish to quantify. If we cannot control the disturbance, then at least we can use pairing and blocking. Pairing is when there is one factor in our experiment; blocking is when we have more than one factor.

5.6.1. Recap of group-to-group differences¶

We have already seen in the univariate statistics section how to analyze this sort of data. We first calculate a pooled variance, then a \(z\)-value, and finally a confidence interval based on this \(z\). Please refer back to that section to review the important assumptions we have to make to arrive at this equation:

We consider the effect of changing from condition A to condition B to be a statistically significant effect when this confidence interval does not span zero. However, the width of this interval and how symmetrically it spans zero can cause us to come to a different, practical conclusion. In other words, we override the narrow statistical conclusion based on the richer information we can infer from the width of the confidence interval and the variance of the process.

5.6.2. Using linear least squares models¶

There’s another interesting way that you can analyze data from an A versus B set of tests and get the identical result to the methods we showed in the section where we made group-to-group comparisons. In this method, instead of using a \(t\)-test, we use a least squares model of the form:

where \(y_i\) is the response variable \(d_i\) is an indicator variable. For example, \(d_i = 0\) when using condition A and \(d_i=1\) for condition B. Build this linear model, and then examine the confidence interval for the coefficient \(g\). The following R function uses the \(y\)-values from experiments under condition A and the values under condition B to calculate the least squares model:

lm_difference <- function(groupA, groupB)

{

# Build a linear model with groupA = 0, and groupB = 1

y.A <- groupA[!is.na(groupA)]

y.B <- groupB[!is.na(groupB)]

x.A <- numeric(length(y.A))

x.B <- numeric(length(y.B)) + 1

y <- c(y.A, y.B)

x <- c(x.A, x.B)

x <- factor(x, levels=c("0", "1"), labels=c("A", "B"))

model <- lm(y ~ x)

return(list(summary(model), confint(model)))

}

brittle <- read.csv('http://openmv.net/file/brittleness-index.csv')

# We developed the "group_difference" function in the Univariate section

group_difference(brittle$TK104, brittle$TK107)

lm_difference(brittle$TK104, brittle$TK107)

Use this function in the same way you did in the carbon dioxide exercise in the univariate section. For example, you will find when comparing TK104 and TK107 that \(z = 1.4056\) and the confidence interval is \(-21.4 \leq \mu_{107} - \mu_{104}\leq 119\). Similarly, when coding \(d_i = 0\) for reactor TK104 and \(d_i = 1\) for reactor TK107, we get the least squares confidence interval for parameter \(g\): \(-21.4 \leq g \leq 119\). This is a little surprising, because the first method creates a pooled variance and calculates a \(z\)-value and then a confidence interval. The least squares method builds a linear model, and then calculates the confidence interval using the model’s standard error.

Both methods give identical results, but by very different routes.

5.6.3. The importance of randomization¶

We emphasized in a previous section that experiments must be performed in random order to avoid any unmeasured, and uncontrolled, disturbances from impacting the system.

The concept of randomization was elegantly described in an example by Fisher in Chapter 2 of his book, The Design of Experiments. A lady claims that she can taste the difference in a cup of tea when the milk is added after the tea or when the tea is added after the milk. By setting up \(N\) cups of tea that contain either the milk first (M) or the tea first (T), the lady is asked to taste these \(N\) cups and make her assessment. Fisher shows that if the experiments are performed in random order, the actual set of decisions made by the lady are just one of many possible outcomes. He calculates all possibilities (we show how below), and then he calculates the probability of the lady’s actual set of decisions being due to chance alone. If the lady has test score values better than by random chance, then there is a reasonable claim the lady is reliable.

Let’s take a look at a more engineering-oriented example. We previously considered the brittleness of a material made in either TK104 or TK107. The same raw materials were charged to each reactor. So, in effect, we are testing the difference due to using reactor TK104 or reactor TK107. Let’s call them case A (TK104) and case B (TK107) so the notation is more general. We collected 20 brittleness values from TK104 and 23 values from TK107. We will only use the first 8 values from TK104 and the first 9 values from TK107 (you will see why soon):

Case A |

254 |

440 |

501 |

368 |

697 |

476 |

188 |

525 |

|

Case B |

338 |

470 |

558 |

426 |

733 |

539 |

240 |

628 |

517 |

Fisher’s insight was to create one long vector of these outcomes (length of vector = \(n_A + n_B\)) and randomly assign “A” to \(n_A\) of the values and “B” to \(n_B\) of the values. One can show that there are \(\dfrac{(n_A + n_B)!}{n_A! n_B!}\) possible combinations. For example, if \(n_A=8\) and \(n_B = 9\), then the number of unique ways to split these 17 experiments into two groups of 8 (A) and 9 (B) is 24,310 ways. For example, one way is BABB ABBA ABAB BAAB, and you would therefore assign the experimental values accordingly (B = 254, A = 440, B = 501, B = 368, A = 697, etc.).

Only one of the 24,310 sequences will correspond to the actual data printed in the above table. Although all the other realizations are possible, they are fictitious. We do this because the null hypothesis is that there is no difference between A and B. Values in the table could have come from either system.

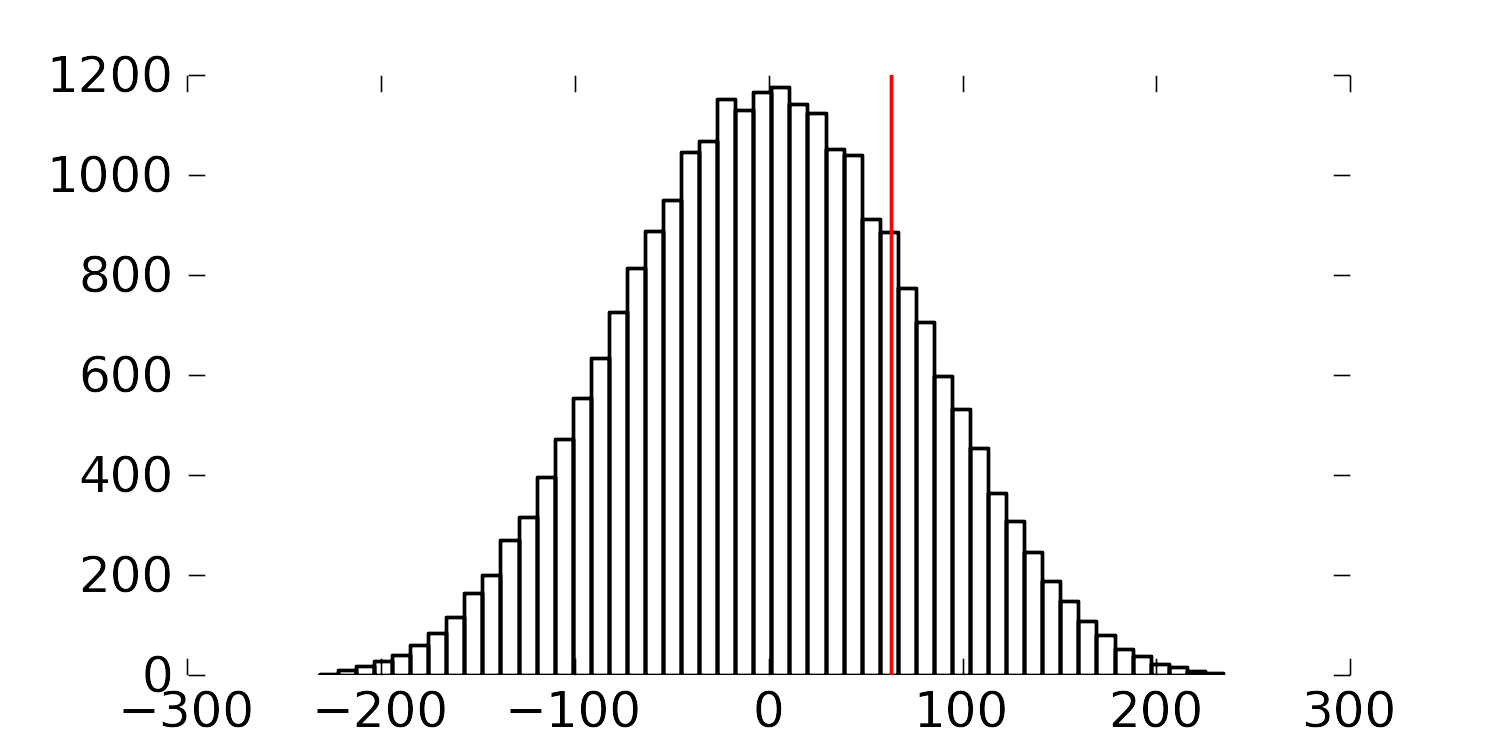

So for each of the 24,310 realizations, we calculate the difference of the averages between A and B, \(\overline{y}_A - \overline{y}_B\), and plot a histogram of these differences. This is shown below, together with a vertical line indicating the actual realization in the table. There are 4956 permutations that had a greater difference than the one actually realized; that is, 79.6% of the other combinations had a smaller value.

Had we used a formal test of differences where we pooled the variances, we would have found a \(z\)-value of 0.8435, and the probability of obtaining that value, using the \(t\)-distribution with \(n_A + n_B - 2\) degrees of freedom, would be 79.3%. See how close they agree?

The figure shows the differences in the averages of A and B for the 24,310 realizations. The vertical line represents the difference in the average for the one particular set of numbers we measured in the experiment.

Recall that independence is required to calculate the \(z\)-value for the average difference and compare it against the \(t\)-distribution. By randomizing our experiments, we are able to guarantee that the results we obtain from using \(t\)-distributions are appropriate. Without randomization, these \(z\)-values and confidence intervals may be misleading.

The reason we prefer using the \(t\)-distribution approach over randomization is that formulating all random combinations and then calculating all the average differences as shown here is intractable. Even on my relatively snappy computer it would take 3.4 years to calculate all possible combinations for the complete dataset: 20 values from group A and 23 values from group B. (It took 122 seconds to calculate a million of them, so the full set of 960,566,918,220 combinations would take more than 3 years.)