5.5. Why learning about systems is important¶

One of the important reasons why we must experiment is that it brings us increased knowledge and a better understanding of our system. That could lead to profit, or it could help us manufacture products more efficiently. Once we learn what really happens in our system, we can fix problems and optimize the system, because we have an improved understanding of cause and effect.

As described in the first reference, the book by Box, Hunter and Hunter, learning from and improving a system is an iterative process. It usually follows this cycle:

Make a conjecture (hypothesis), which we believe is true.

If it is true, we expect certain consequences.

Experiment and collect data. Are the consequences that we expected visible in the data?

If so, it may lead to the next hypothesis. If not, we formulate an alternative hypothesis. Or perhaps it is not so clear cut: we see the consequence, but not to the extent expected. Perhaps modifications are required in the experimental conditions.

And so we go about learning. One of the most frequent reasons we experiment is to fix a problem with our process. This is called troubleshooting. We can list several causes for the problem, change the factors, isolate the problem, and thereby learn more about our system while fixing the problem.

5.5.1. An engineering example¶

Let’s look at an example. We expect that compounds A and B should combine in the presence of a third chemical, C, to form a product D. An initial experiment shows very little of product D is produced. Our goal is to maximize the amount of D. Several factors are considered: temperature, reaction duration and pressure. Using a set of structured experiments, we can get an initial idea of which factors actually impact the amount of D produced. Perhaps these experiments show that only temperature and reaction duration are important and that pressure has little effect. Then we go ahead and adjust only those two factors, and we keep pressure low (to save money because we can now use a less costly, low-pressure reactor). We repeat several more systematic response surface experiments to maximize our production goal.

The iterations continue until we find the most economically profitable operating point. At each iteration we learn more about our system and how to improve it. The key point is this: you must disturb your system, and then observe it. This is the principle of causality, or cause and effect.

It is only by intentional manipulation of our systems that we learn from them. Collecting happenstance data, (everyday) operating data, does not always help, because it is confounded by other events that occur at the same time. Everyday, happenstance data is limited by feedback control systems.

5.5.2. Feedback control¶

Feedback control systems keep the region of operation to a small zone. Better yields or improved operation might exist beyond the bounds created by our automatic control systems. Due to safety concerns, and efficient manufacturing practices, we introduce automated feedback control systems to prevent deviating too far from a desired region of operation. As a result, data collected from such systems has low information quality.

An example would be making eggs for breakfast. If you make eggs the same way each morning (a bit of butter, medium heat for 5 minutes, flip and cook it for 1 minute, then eat), you will never experience anything different. The egg you make this morning is going to taste very similar to one last year, because of your good control system. That’s happenstance data.

You must intentionally change the system to perturb it, and then observe it.

5.5.3. Another engineering example¶

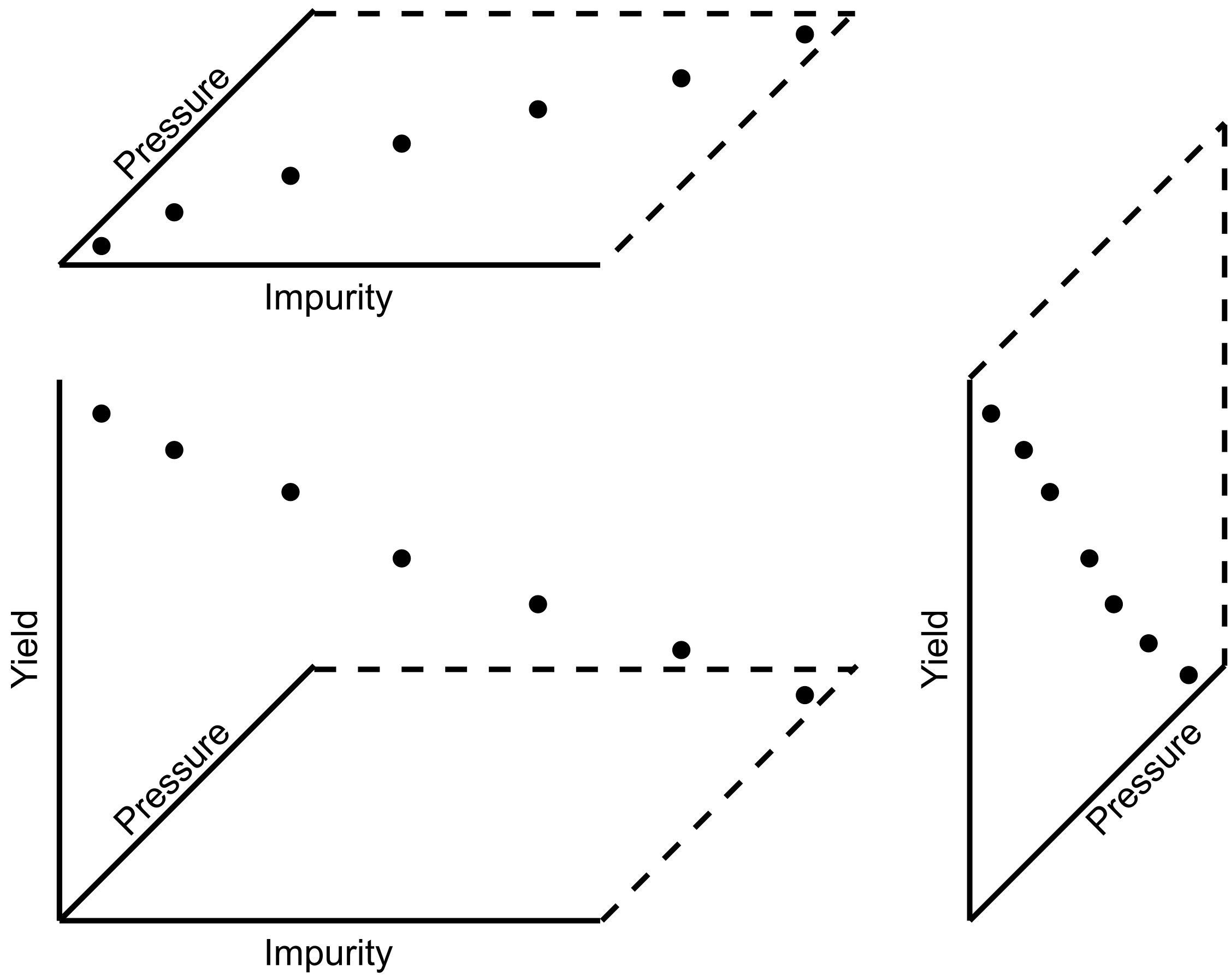

Here’s a great example from the book by Box, Hunter and Hunter. Consider the negative-slope relationship between pressure and yield: as pressure increases, the yield drops. A line could be drawn through the points from the happenstance measurements, taken from the process at different times in the past. That line could be from a least squares model. It is true that the observed pressure and yield are correlated, as that is exactly what a least squares model is intended for: to quantify correlation.

The true mechanism in this system is that pressure is increased to remove the frothing that occurs in the reactor. Higher frothing occurs when there is an impurity in the raw material, so operators increase reactor pressure when they see frothing (i.e. high impurity). However, it is the high impurity that actually causes the lower yield, not the pressure itself. These relationships between yield, pressure and impurity levels are illustrated below, based an adaption from the book by Box, Hunter and Hunter, Chapter 14 (1st edition) or Chapter 10 (2nd edition).

Pressure is correlated with the yield, but there is no cause-and-effect relationship between them. The happenstance relationship only appears in the data because of the operating policy, causing them to be correlated, but it is not cause and effect. That is why happenstance data cannot be relied on to imply cause and effect. An experiment in which the pressure is changed from low to high, performed on the same batch of raw materials (i.e. at constant impurity level), will quickly reveal that there is no causal relationship between pressure and yield.

Another problem with using happenstance data is that they are not taken in random order. Time-based effects, such as changes in the seasonal or daily temperatures, will affect a process. We are all well aware of slow changes: fridges and stoves degrade over time, cars need periodic maintenance. Even our human bodies follow this rule. If we do not randomize the order of experiments, we risk inferring a causal relationship when none actually exists.

Designed experiments are the only way we can be sure that these correlated events are causal. You often hear people repeat the (incomplete) phrase that “correlation does not imply causality”. That is only half-true: the other half of the phrase is “correlation is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for causality”.

In summary, do not rely on anecdotal “evidence” from colleagues. Always question the system, and always try to perturb the system intentionally. In practice you won’t always be allowed to move the system too drastically, so at the end of this chapter we will discuss response surface methods and evolutionary operation, which can be implemented on-line in production processes.

Experiments are the most efficient way to extract information about a system, that is, the most information in the fewest number of changes. So it is always worthwhile to experiment.