4.11. Outliers: discrepancy, leverage, and influence of the observations¶

Unusual observations will influence the model parameters and also influence the analysis from the model (standard errors and confidence intervals). In this section we will examine how these outliers influence the model.

Outliers are in many cases the most interesting data in a data table. They indicate whether there was a problem with the data recording system, they indicate sometimes when the system is operating really well, though more likely, they occur when the system is operating under poor conditions. Nevertheless, outliers should be carefully studied for (a) why they occurred and (b) whether they should be retained in the model.

4.11.1. Background¶

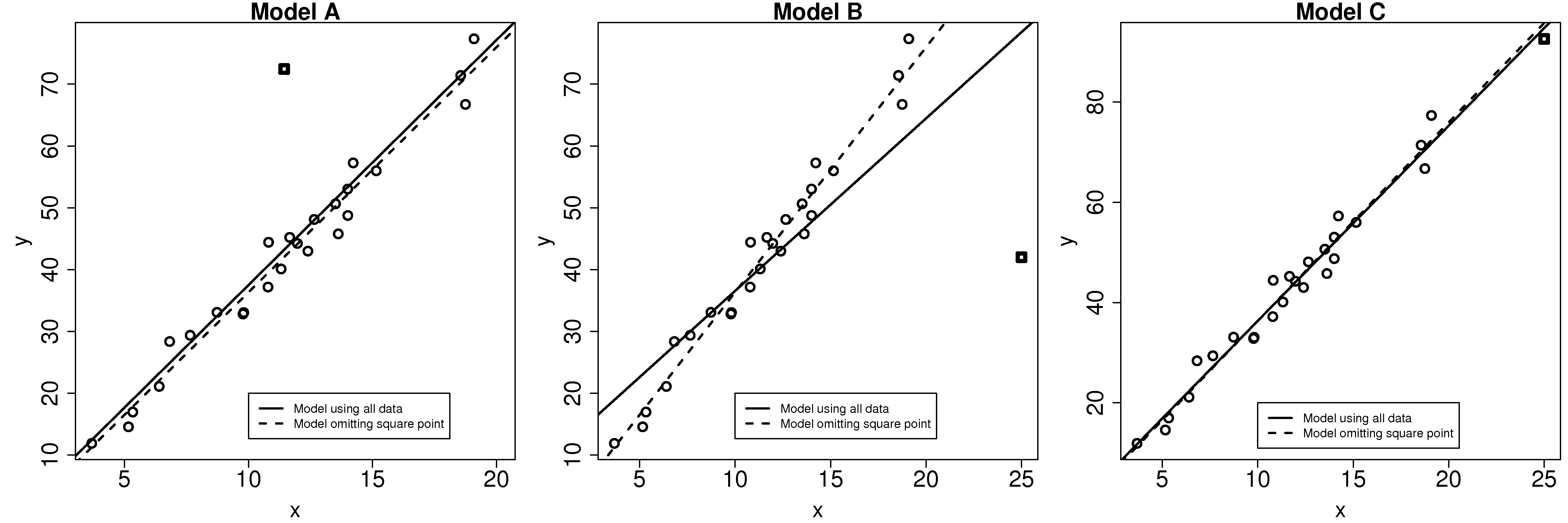

A discrepancy is a data point that is unusual in the context of the least squares model, as shown in the first figure here. On its own, from the perspective of either \(\mathrm{x}\) or \(\mathrm{y}\) alone, the square point is not unusual. But it is unusual in the context of the least squares model. When that square point is removed, the updated least squares line (dashed line) is obtained. This square point clearly has little influence on the model, even though it is discrepant.

The discrepant square point in model B has much more influence on the model. Given that the objective function aims to minimize the sum of squares of the deviations, it is not surprising that the slope is pulled towards this discrepant point. Removing that point gives a different dashed-line estimate of the slope and intercept.

In model C the square point is not discrepant in the context of the model. But it does have high leverage on the model: a small change in this point has the potential to be influential on the model.

Can we quantify how much influence these discrepancies have on the model; and what is leverage? The following general formula is helpful in the rest of this discussion:

\[\text{Leverage} \times \text{Discrepancy} = \text{Influence on the model}\]

4.11.2. Leverage¶

Leverage measures how much each observation contributes to the model’s prediction of \(\hat{y}_i\). It is also called the hat value, \(h_i\), and simply measures how far away the data point is from the center of the model, but it takes the model’s correlation into account:

\[h_i = \dfrac{1}{n} + \dfrac{\left(x_i -\overline{x}\right)^2}{\sum_{j=1}^{n}{\left(x_j -\overline{x}\right)^2}} \qquad \text{and}\qquad \overline{h} = \dfrac{k}{n} \qquad \text{and}\qquad \dfrac{1}{n} \leq h_i \leq 1.0\]

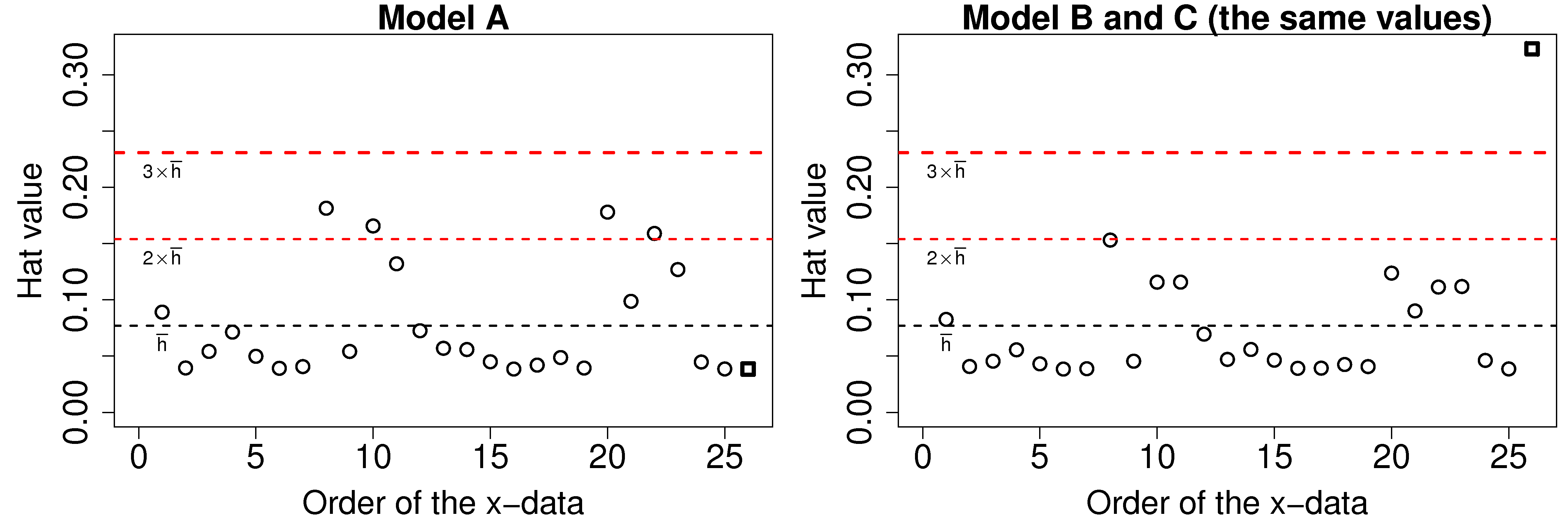

The average hat value can be calculated theoretically. While it is common to plot lines at 2 and 3 times the average hat value, always plot your data and judge for yourself what a large leverage means. Also notice that smallest hat value is always positive and greater or equal to \(1/n\), while the largest hat value possible is 1.0. Continuing the example of models A, B and C: the hat values for models B and C are the same, and are shown here. The last point has very high leverage.

4.11.3. Discrepancy¶

Discrepancy can be measured by the residual distance. However the residual is not a complete measure of discrepancy. We can imagine cases where the point has such high leverage that it drags the entire model towards it, leaving it only with a small residual. One way then to isolate these points is to divide the residual by \(1-\text{leverage} = 1 - h_i\). So we introduce a new way to quantify the residuals here, called studentized residuals:

\[e_i^* = \dfrac{e_i}{S_{E(-i)}\sqrt{1-h_i}}\]

Where \(e_i\) is the residual for the \(i^\text{th}\) point, as usual, but \(S_{E(-i)}\) is the standard error of the model when deleting the \(i^\text{th}\) point and refitting the model. This studentized residual accounts for the fact that high leverage observations pull the model towards themselves. In practice the model is not recalculated by omitting each point one at a time, rather there are shortcut formula that implement this efficiently. Use the rstudent(lm(y~x)) function in R to compute the studentized residuals from a given model.

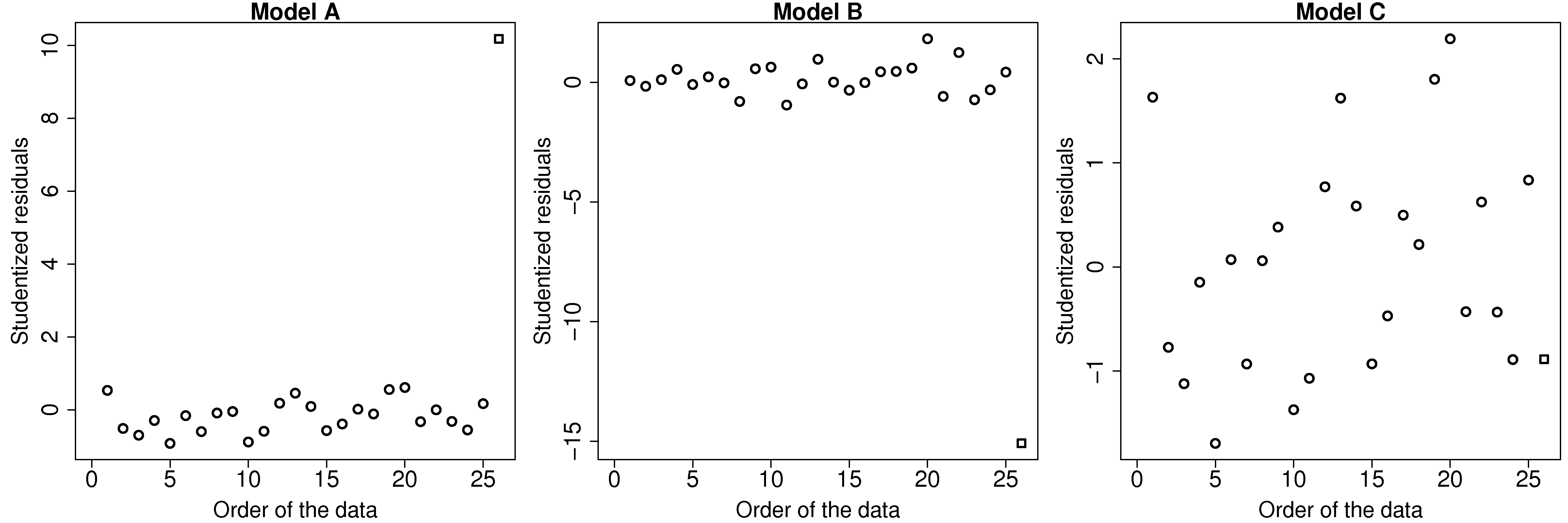

This figure illustrates how the square point in model A and B is highly discrepant, while in model C it does not have a high discrepancy.

4.11.4. Influence¶

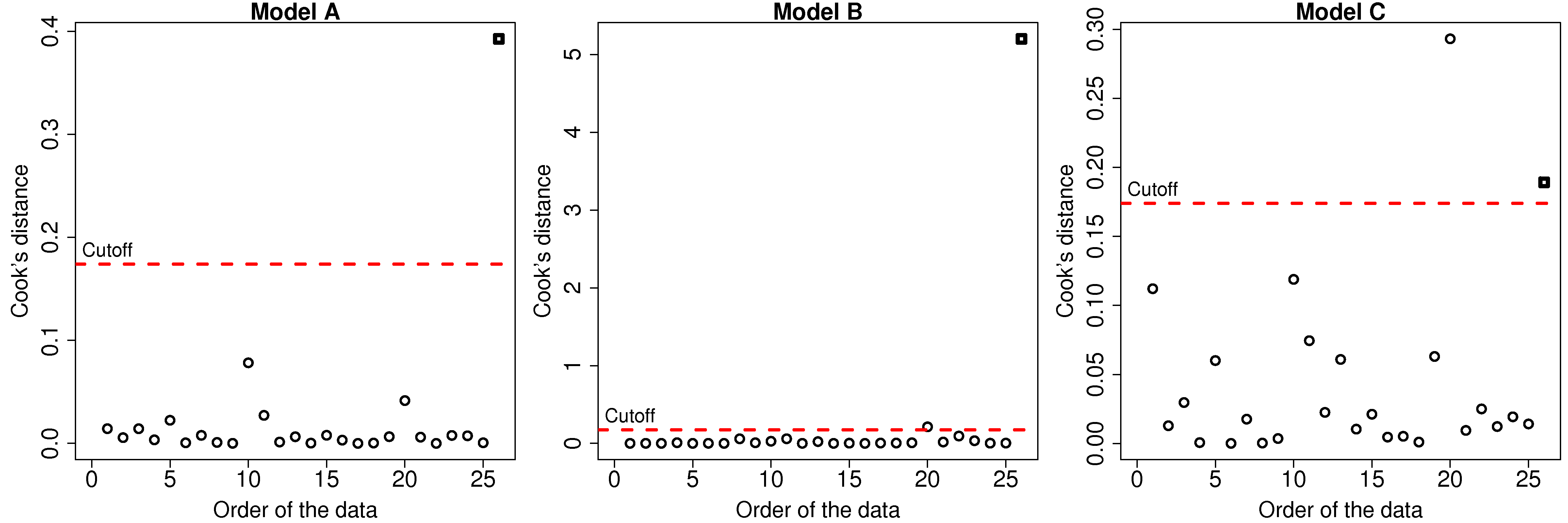

The influence of each data point can be quantified by seeing how much the model changes when we omit that data point. The influence of a point is a combination its leverage and its discrepancy. In model A, the square point had large discrepancy but low leverage, so its influence on the model parameters (slope and intercept) was small. For model C, the square point had high leverage, but low discrepancy, so again the change in the slope and intercept of the model was small. However model B had both large discrepancy and high leverage, so its influence is large.

One measure is called Cook’s statistic, usually called \(D_i\), and often referred to just as Cook’s D. Conceptually, it can be viewed as the change in the model coefficients when omitting an observation, however it is much more convenient to calculate it as follows:

\[D_i = \dfrac{e_i^2}{k \times \frac{1}{n}\sum{e_i^2}} \times \dfrac{h_i}{1-h_i}\]

where \(\frac{1}{n}\sum{e_i^2}\) is called the mean square error of the model (the average square error). It is easy to see here now why influence is the product of discrepancy and leverage.

The values of \(D_i\) are conveniently calculated in R using the cooks.distance(model) function. The results for the 3 models are shown. Interestingly for model C there is a point with even higher influence than the square point. Can you locate that point in the least squares plot?