5.8.4. Analysis by least squares modelling¶

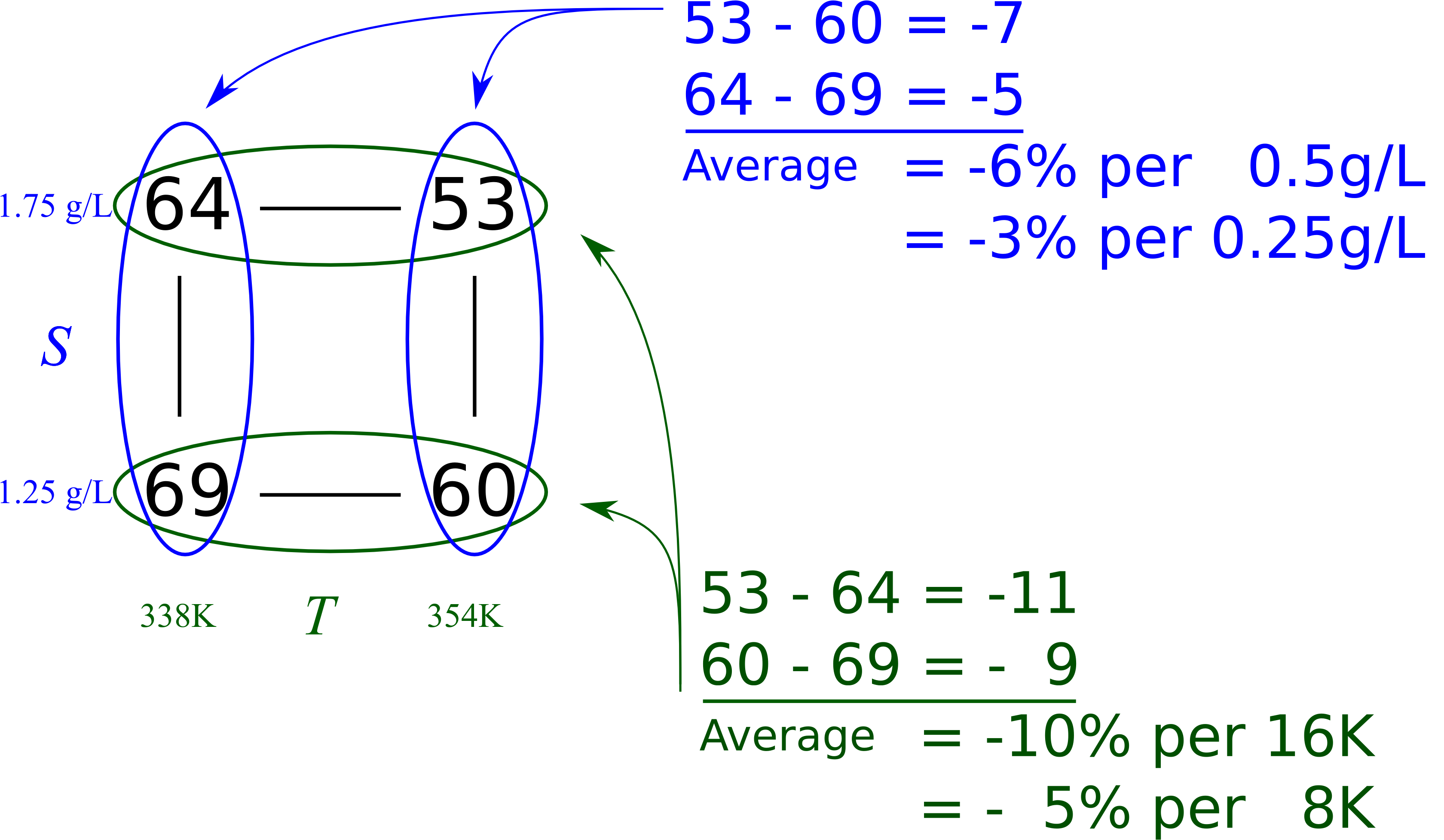

Let’s review the original system (the one with little interaction) and analyze the experimental data using a least squares model. We represent the original data here, with the baseline conditions:

Experiment

[K]

[g/L]

[%] Baseline

346 K

1.50

1

(338 K)

(1.25 g/L) 69

2

(354 K)

(1.25 g/L) 60

3

(338 K)

(1.75 g/L) 64

4

(354 K)

(1.75 g/L) 53

It is standard practice to represent the data from designed experiments in a centered and scaled form:

Similarly,

We will propose a least squares model that describes this system:

We have four parameters to estimate and four data points. This means when we fit the model to the data, we will have no residual error, because there are no degrees of freedom left. If we had replicate experiments, we would have degrees of freedom to estimate the error, but more on that later. Writing the above equation for each observation,

Where the last line is a more compact representation. Notice then that the matrices from linear regression are:

Some things to note are (1) the orthogonality of

Note how the

What is the interpretation of, for example,

Similarly, the slope coefficient for

Now contrast these numbers with those in the graphical analysis done previously and repeated below. They are the same, as long as we are careful to interpret them as the change over half the range.

The 61.5 term in the least squares model is the expected conversion at the baseline conditions. Notice from the least squares equations how it is just the average of the four experimental values, even though we did not actually perform an experiment at the center.

Let’s return to the system with high interaction where the four outcome values in standard order were

77, 79, 81 and 89. Looking back, the baseline operation was

The interaction term can now be readily interpreted: it is the additional increase in conversion seen when both temperature and substrate concentration are at their high level. If

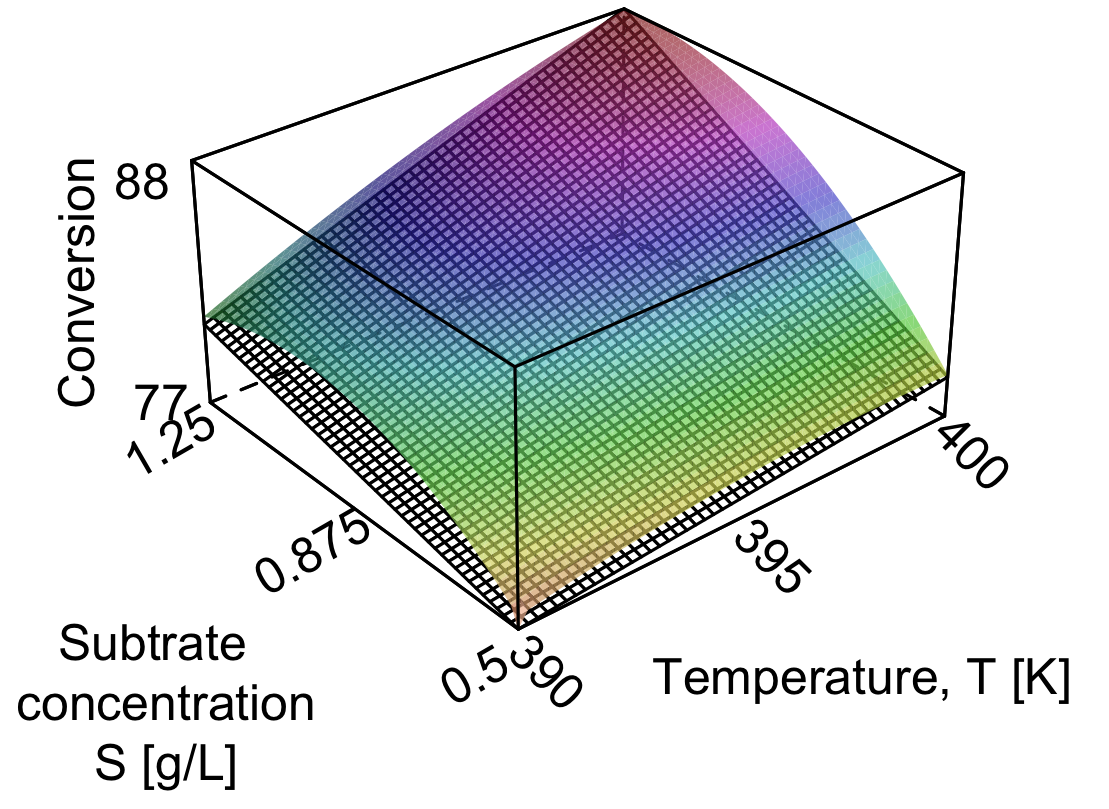

Finally, out of interest, the nonlinear surface that was used to generate the experimental data for the interacting system is coloured in the illustration. In practice we never know what this surface looks like, but we estimate it with the least squares plane, which appears below the nonlinear surface as black and white grids. The corners of the box are outer levels at which we ran the factorial experiments.

The corner points are exact with the nonlinear surface, because we have used the four values to estimate four model parameters. There are no degrees of freedom left, and the model’s residuals are therefore zero. Obviously, the linear model will be less accurate away from the corner points when the true system is nonlinear, but it is a useful model over the region in which we will use it later in the section on response surface methods.